At least 15,000 foreign fighters, around 2000 of them from western nations, have left their home countries to go fight on behalf of ISIS in Syria or Iraq. Yet that estimate, widely repeated in the press, is months old, and so the number is probably somewhat higher in both cases. What hasn’t been reported on much until fairly recently, is the phenomenon of foreign fighters, particularly from the west, who have gone to Syria or Iraq to join the fight against ISIS. Indeed, there have been some westerners, driven by various motivations, who have traveled to the region to support and join Kurdish fighters on the ground. They are not mercenaries, so far as we know, doing this for financial gain. Rather, they claim far more altruistic motives and are doing this at their own expense.

A recent article by Crispian Cuss on Al-Jazeera, about two British men who have joined the Kurds in their fight against ISIS, highlights this issue. Titled A Very Secular Jihad, Cuss describes how two Britons, Jamie Read and James Hughes, have banded with other foreign fighters (including Americans and Canadians) who have joined up with the so-called Kurdish People’s Protection Units, which have been key in the effort to defend northern Syria from the expansion of ISIS into the region.

As for Read and Hughes’ motives, Cuss notes:

“Under the banner of Edmund Burke’s quote that, “All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing,” the western fighters spell out their motives in a Facebook post writing that: ‘They will not do nothing while innocent Kurdish men, women and children, Yazidis, Shia and Sunni Muslims, Christians and regional minorities of all kinds are tortured and murdered by Islamic State.’”

A few things interested me about this topic. The first thing was the idea of elective participation in wars. When the governments of nation-states go to war, the men and women serving in the military have little say about it. In the U.S., when the president, as Commander and Chief, orders forces into battle, legally they must go, regardless of how they feel personally or morally about the war. But in the case of the war with ISIS, westerners on both sides have made personal decisions to commit to one side or the other, travel to join them, and fund their efforts on their own. In some ways, this approach directly addresses some common criticisms of those who oppose military intervention at home. The only lives threatened in this case are only those who want to go. It also eliminates criticism concerning the expense of engaging in military conflicts, as such efforts are personally funded and financed only by those who choose to go, rather than taxpayer dollars.

I suppose this is one way of getting around one’s home government’s lack of action (if one feels their government is not doing enough). Many Americans, for example, deeply disturbed about many reports of atrocities committed by ISIS, feel that the U.S. bombing campaigns are not enough and some have advocated putting U.S. troops on the ground. But most U.S. politicians, after a decade of warfare in the Middle East, are aware of the broader exhaustion of the American people to such commitments in the region. Moreover, when individuals make such efforts on a personal level, they are acting in contrast to the foreign policy of their government, which can lead to legal problems for them and potential headaches for their governments abroad.

These issues aside, I also could not help but think of historical examples from the past where similar efforts have been made by individuals who made decisions to participate in wars as individuals, not as members of their home nation’s military, and fund those efforts on their own. Cuss draws an interesting comparison as well to the Spanish-Civil War of the 1930s, in which thousands of Europeans from many countries, most famously (perhaps) the British author George Orwell, committed themselves to one side or the other because of their personal beliefs. Yet such a phenomenon is much older than the 20th century. Indeed, as someone who studies the crusades, I could not help but think of some limited parallels with the early crusading movement, particularly the First Crusade, prior to it becoming more professionalized in the later crusading era.

Consider Read and Hughes’ motivations, as laid out in their Facebook post cited above. They note they are joining the Kurds in their war against ISIS because of atrocities carried out by the group against people of different religions (Christians and Yazidis) or co-religionists with different religious or political views (Kurds, Shia and some Sunni Muslims). Moreover, they highlight ISIS’ abuse of women and children, which has been widely documented by the press. They contrast this with the Burke quote that explicitly suggests such behavior is evil, and cannot be allowed to go unchecked, and so for these reasons, they have decided to join the fight. But the key point expressed here is that, for them, it is a fight against evil.

While many in the modern west have very negative understandings of the motives of the medieval crusaders, often claiming their chief goal was to acquire wealth at the expense of Muslims in the Holy Land, modern crusades scholarship has, since at least the 1970s, largely abandoned such a view. Instead, while there may be some exceptions, the evidence seems to show most crusaders were motivated instead by spiritual reasons.

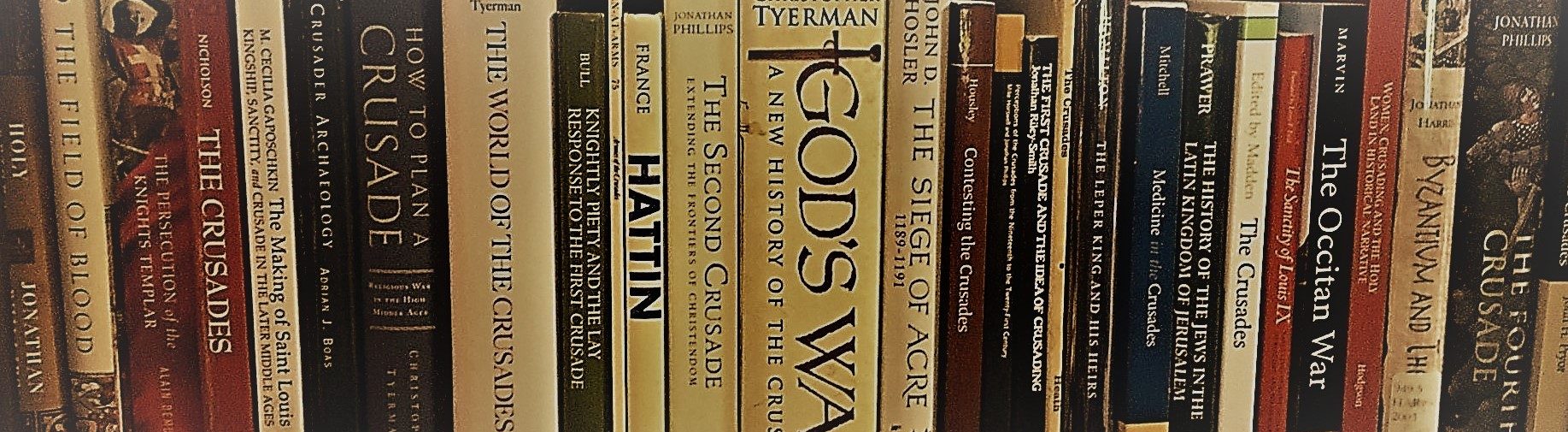

As is commonly known among modern crusades scholars, crusading was massively expensive for those who participated, sometimes bankrupting those who chose to participate (yes, chose, as it was optional. Scholars estimate only about 1% to 2% of Europe’s knights ever participated in a crusade). Like the modern Britons Read and Hughes, those who took vows to participate in the First Crusade had to fund themselves and it was very expensive. They had to pay for their own travel across continents, lasting for years, as well as their own weapons, armor, and supplies during the expedition. Many had to borrow funds and go into debt to commit to such a venture. Once they had fulfilled their crusading vows, the vast overwhelming majority returned home quickly, worried about the state of their lands, titles, and other possessions after such a lengthy absence. Moreover, many were knights, who knew well the costs of warfare for such an extended term, so they were not caught unaware. The surviving charters of the departing knights, in some ways the medieval equivalent of Read and Hughes’ Facebook post justifying their reasons for going to Syria, expressed the anxiety of such knights about the costs rather than their hope of riches. Nevertheless, they made the choice to join the crusade and accept all the burdens that entailed. Such financial hardships and concerns have been well documented in the works of retired Cambridge University historian Jonathan Riley-Smith and current UNC-Chapel Hill Professor Marcus Bull (among many others).

Thus, rather than financial gain, modern historians have argued (for this and other reasons) that other causes played a much greater role in the motivations of such men to join a crusade. They certainly gained a spiritual benefit in joining a crusade, as Popes promised them crusading indulgences for their suffering during their service to the cross (about 1/3 of all knights died during the First Crusade), which could lessen the penance they owed for previously confessed and forgiven sins. Moreover, the clergy told such knights that the crusade would represent a war against evil, and told terrible stories of the abuse of eastern Christians at the hands of the Turks, who had recently expanded their rule into Byzantine Christian lands through warfare and conquest.

According to one account (by Fulcher of Chartres) of Pope Urban II’s speech at Clermont in 1095 calling for what would become known as the First Crusade, the Pope is reported to have told the knights in attendance:

“For your brethren who live in the east are in urgent need of your help, and you must hasten to give them the aid which has often been promised them. For, as the most of you have heard, the Turks and Arabs have attacked them and have conquered the territory of Romania [the Greek empire] as far west as the shore of the Mediterranean and the Hellespont, which is called the Arm of St. George. They have occupied more and more of the lands of those Christians, and have overcome them in seven battles. They have killed and captured many, and have destroyed the churches and devastated the empire. If you permit them to continue thus for awhile with impurity, the faithful of God will be much more widely attacked by them.”

Such rhetoric and stories are not unlike those we hear today about ISIS, and it’s atrocities against religious minorities and others in Syria and Iraq. Indeed, the abuse of eastern Christians by the Turks was a major theme found in the charters of knights who agreed to participate in the First Crusade, justifying their reasons for doing so. A charter of two brothers, for example, written shortly before they embarked on the First Crusade, notes that they were going on the crusade, in part, “…to wipe out the defilement of the pagans and the immoderate madness through which innumerable Christians have already been oppressed, made captive and killed with barbaric fury.” (See Riley-Smith, The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading, 23-24).

The view of these two crusading brothers is obviously very similar to that expressed by Read and Hughes in their Facebook post, which justified their reasons for going to wage war against ISIS. Indeed, like the crusaders, Read and Hughes had a choice in whether they would wage war on behalf of their chosen cause, and had to fund it themselves, and they did so for reasons not unlike those of the earliest crusaders. This is not to say that Read and Hughes are the equivalent of medieval crusaders. They aren’t. To be clear, there are MANY differences, of course, between the two situations. But there are also some interesting parallels.

Andrew Holt