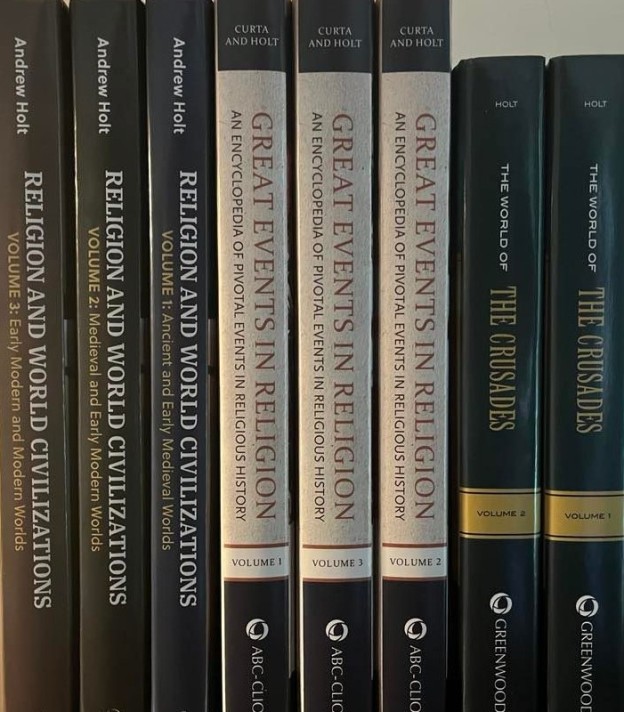

Having recently received hardback copies of a third multivolume encyclopedia that I have either edited or authored, I sometimes get questions about the process. Frankly, there are not a lot of written resources for academics considering taking on such a project for the first time, but you can count on senior scholars to share their wisdom. For example, I was fortunate enough to be able to discuss my various projects with my friend, Alfred J. Andrea, a master encyclopedist, and co-edit my first encyclopedia with my former dissertation advisor, Florin Curta, a leading scholar of the early Middle Ages. In this, I have been fortunate to have such guidance, and so want to share a bit of what I have learned about the process.

It’s important to note that one’s experience editing (or authoring) such a project can vary quite a bit from project to project. It depends on one’s goals from the outset, your level of commitment, the level of support from the publisher, and whether or not there is a global pandemic that shuts down all the universities and makes many of your contributors sick while you are trying to complete the task (yes, it happened). These variables aside, while fully acknowledging that other encyclopedists may disagree with me on some finer points, there are some general considerations that I feel confident sharing here.

In what is surely one of the least exciting possible blog posts with the smallest possible target audience since I began blogging, I reflect on some of those considerations in encyclopedia editing here. Hopefully, they will be of use to those few brave souls considering taking on such a project.

Do you want to edit an encyclopedia or write it yourself?

If you take on a large, broad-based project, with multiple volumes and hundreds, or even thousands, of entries scattered over time and place, you will likely want to recruit qualified contributors and edit the project. For example, most recently, I edited a three-volume work on how religion has influenced various societies globally from antiquity to the present, which included over 500 entries. Such an endeavor is all about project management. No single scholar has the expertise to write all those wildly varying entries with any degree of certainty that they are aware of the latest historiography on each of the various topics. Were they to commit to researching what scholars are currently writing about the topic, the project would consume a massive amount of time, which few (if any) academic publishers, who prefer keeping to a timely schedule, would be willing to grant.

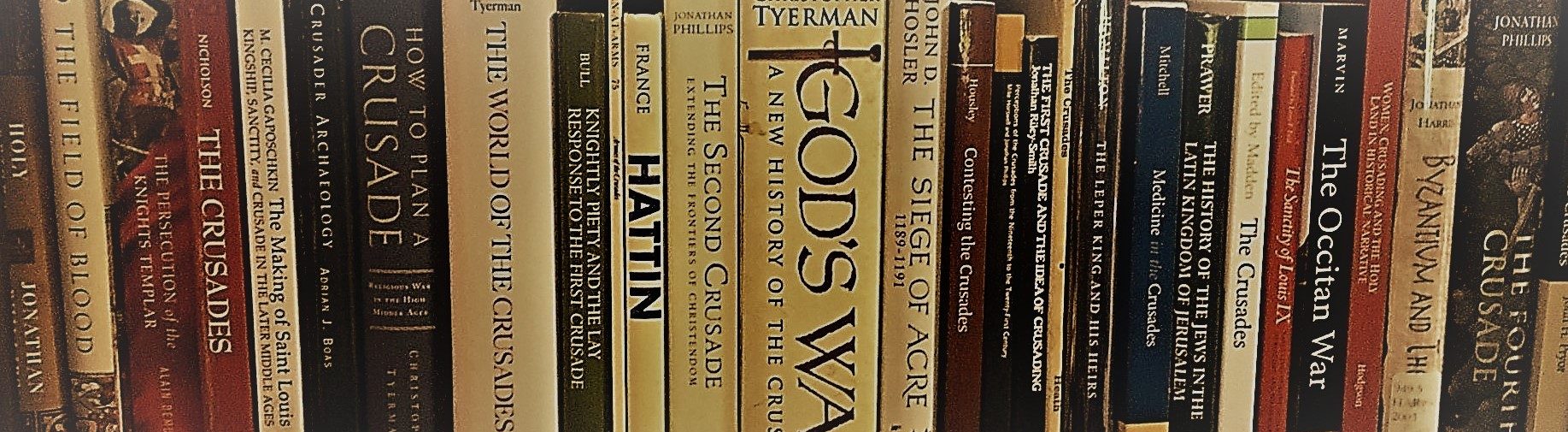

If your project is not so grandiose, and much more narrowly focused and manageable (one or two volumes), then you might consider writing all the entries yourself. For example, I used this approach in a two-volume encyclopedia on the crusades, a topic to which I have dedicated most of my adult life. Because I chose the entries, I could also select those that I either had a solid familiarity with, or those for which I knew where to look for the most recent scholarship. Writing all the entries myself also ensured consistency, both in terms of the claims made across entries as well as writing style. Nevertheless, it seemed like a herculean task at times, writing hundreds of small essays, not to mention constant editing and revisions, over the course of a year or so, and resulted in many nearly sleepless nights to stay on schedule. I also reached out to, and pestered, a number of friends who are crusade historians, promising them many steak dinners at future conferences. I still need to make good on some of those dinners.

Scholars make mistakes, so make sure to do three things: fact check, fact check, fact check.

Often, such errors are simple oversights, such as a reversed date, misspelled names, or confusion over the proper author of a work they mention. It’s been my experience that once you submit a completed manuscript, the publisher’s editors will dig carefully into such things and root out whatever you may have missed in your initial editing, but the more you can eliminate up front, the better. Moreover, the publisher’s fact-checkers are not infallible and often they usually have no expertise in the field covered by the encyclopedia. Trust no one.

Be prepared: editing is tough work.

Proper editing requires a massive amount of work, time, and patience, as in some cases multiple revisions (requiring multiple back and forth emails between the editor and contributor) can take place for a small encyclopedia entry. When this happens, you, as the editor, will wish you had been a bit more selective in your recruitment of contributors.

Recruitment of contributors.

Recruitment of contributors is important for several reasons, the most obvious being even the most well informed and energetic editor can only do so much. The most important things to look for in potential contributors are their awareness of the topic they are writing about, their writing ability, and their responsiveness to editorial concerns. Some of these concerns can be mitigated if you, as editor, have a deep awareness of the topic assigned to the contributor, and can aggressively edit any submissions, policing them for content and technical issues. For example, I would not be overly concerned about assigning an essay on the crusades to a junior graduate student, simply because I can confidently and robustly revise the essay as needed since this is my area of research. No sweat. I would be far less confident with other topic areas.

Awareness- Do they have a research background on the topic of the entry they are writing about? Perhaps they have published a recent book or article on some aspect of the topic. Or, if they are a doctoral student, perhaps they are in the middle of writing a dissertation on the topic. If none of the above, are they a competent historian with an interest in the topic and willing to research the historiographical background of the topic properly before writing their essay?

Writing ability- encyclopedia articles are not always easy for academics to write. One has to take a complex topic and distill it down into a short essay that is digestible for the target audience. While scholars write for other scholars and graduate students in academic journals and monographs, encyclopedia articles generally target undergraduates and informed general readers. Indeed, as I understand it, academic presses often commission expensive encyclopedias because they hope to sell them to libraries with large purchasing budgets, that will include them in their reference sections. Thus, writers of encyclopedia articles, offering an introduction to a topic, cannot assume even basic background knowledge on the part of a reader.

Responsiveness- If you are fortunate enough to recruit senior scholars to contribute an essay or two to your work, they are not always very receptive to editorial feedback. After all, they may be among the leading scholars in the world on your topic, and you, as the editor specialize in something else. You often must be willing to trust their judgment on subject matter, which you should be fine with doing. After all, it is their names signed at the bottom of the entry and they are the experts, but, nevertheless, nothing prevents you from quietly fact checking. Every scholar stumbles at some time or another.

Moreover, an editor should not be shy about wrangling, hopefully gently, with a senior scholar over how an issue is framed considering the target audience. Is their piece digestible to a non-specialist? If not, it will need some tweaking and hopefully the senior scholar has no objections, but sometimes they do. I often do the editing myself and send them a draft so that they can see nothing substantial has been changed and they do not need to do further work (only approve the revised draft). In the vast majority of cases, they are fine with this.

Pros and cons of senior scholars and Ph.D. students as contributors.

Ph.D. students are often more enthusiastic about contributing. They may be in the midst of writing their dissertation about the topic of an entry in your encyclopedia, and so they have been immersed in its sources and recent historiography and feel as though they can write a decent short essay quite easily (which is often true). Moreover, they will be graduating, eventually, and looking for a job, and so it is important to them to add academic publications to their budding curricula vitarum,[1] even minor ones, like encyclopedia entries. Once the encyclopedias are published with their essays, they tend to tag me a lot on social media, as they celebrate seeing their work in print. It’s genuinely one of the nicer aspects of editing an encyclopedia. They also tend to respond well to feedback and revisions and typically, not always, complete their essays relatively soon. Yet, for all of their wonderful enthusiasm, the quality of their writing (especially initial drafts) can sometimes be poor (requiring a lot of editing), and they tend to make (but not always) more basic factual errors in comparison to senior scholars. After all, Ph.D. students typically have only a couple of years of intensive study of a topic, while senior scholars have often devoted most of their adult life to it.

Senior scholars can usually be trusted with the topics they write about for reasons stated earlier. Plus, if they are willing to contribute an essay or two, they lend the weight of their (sometimes stellar) reputation, to some degree, to the encyclopedia. Indeed, in recruiting contributors, I would often highlight the participation of leading scholars to recruit other leading scholars, and it seems to have been effective. They might respond with “Oh, so and so is contributing an essay? What are they writing about? Oh, that makes sense. Well, let me take a look at your little list.” Once they have looked at the list, they sometimes suggest helpful additions for essays, which I enthusiastically entertain, before finally asking them if they will write them. They might dryly respond with something along the lines of “I walked right into that, didn’t I?”

Senior scholars do not typically abide by the proposed deadlines, so be prepared to wait until they are ready to send in their essays, but they typically tolerate gentle prodding by the editor, which might help. They also do not worry about the proposed formats of the essay. “You’re the editor. You can sort it out and format it as you think best.” Nor do they always abide by the rough word limits proposed for the essays. In one extreme case, I once assigned a 1,000-word essay to a senior scholar, a leading European historian of the early Middle Ages, and he returned an essay six months overdue with over 4,400 words. When I responded with a request to reduce the length of the essay “a bit,” he seemed offended at the suggestion, asking me if I wanted “quality work or not?” He was certainly right that it was a very nice essay, and I would have loved to have been able to publish the whole thing, but I could not. He did not care that the word limits exist for a reason and the publisher often insists on them. After gentle and lengthy negotiations, and a lot of work on both our parts, we were able to reduce the word count to 2,400 words, which I made room for by eliminating other essays that had not been written. In hindsight, I must have really wanted to include his work.

Some scholars, even noteworthy ones, plagiarize.

Sadly, some scholars, including those holding tenured positions at universities or colleges, openly plagiarize materials they find online. To be clear, most scholars adhere to a professional code of ethics that prevents this sort of thing, but, unfortunately, there are some rascals. When this happens, it is massively frustrating for the editor for multiple reasons.

First, it embarrasses both parties, the editor and the contributor, if they know each other and were friendly prior to embarking on the project. In the aftermath of discovering plagiarism and removing a contributor from a project, I hope I will not have to run into them at conferences in the future, which would be very awkward. Heaven forbid we ever end up sharing a cab from the airport to the same hotel when attending an out-of-town conference.

Second, when contributors who plagiarize are discovered, they know it can damage their reputations if news of it gets out, and, thus, they generally take one of two approaches in their response, either expressing great remorse (e.g. they are very sorry, but going through a tough time personally at the moment, etc…) or angry defiance (e.g. they are offended that I brought it up and threaten to quit the project, threaten me if I say anything about it, etc…). For the record, in a final email I simply tell them, depending on how clear-cut and obvious their plagiarism is (e.g. they obviously copied and pasted multiple paragraphs verbatim from an online source), that we will not be publishing their essays. They rarely have responded to this final email, which ends the dialogue.

Third, their plagiarism can also delay the project. Once discovered, you, as editor, cannot publish their work, so you need to go back and recruit additional contributors who will take over these topics. Also, if discovered late in the process, this can really upset the publisher. Once, when co-editing a three-volume encyclopedia, we depressingly discovered that a Ph.D. student who had enthusiastically contributed several essays had plagiarized several parts of them, right as we were about to submit the final (Hallelujah!) manuscript to the publisher (who was calling for it as it was overdue). We fired the contributor after warning him about the damage this could do to his career and deleted his essays from the work. We did not have time to recruit new authors and give them several months to write and submit new essays, so we researched and wrote at least some replacements that we felt absolutely needed to be included in the final work. It was quite a headache.

Fourth, publishers, who can be liable for plagiarism, take this very seriously. Acquisitions editors will not work with known plagiarizers. The publisher does not want to have to scrap a recently printed book, which they have invested a lot of money and resources into, because plagiarism is discovered (but they will). Moreover, they employ fact checkers who often find online sources (they also use Google) from which the contributor plagiarized. Publishers also use the new technologies available to weed out possible plagiarism hidden away in massive works like multivolume encyclopedias. I often tell my students that plagiarizing is not worth it because the penalties are so severe if you get caught, and the chances of getting caught are increasingly high due to new technologies. Sadly, I worry that I may have to give the same warning to some professors and graduate students.

Pay and compensation

Encyclopedists don’t do it for the money. Far too many hours are put into editing a multivolume encyclopedia to be reasonably compensated. I have often joked with my wife that if I put the same number of hours into a minimum wage job as I do into an encyclopedia, which usually takes years to complete, I would make more money with the minimum wage job. I have a friend and senior colleague that thinks that with all his editing over the course of his lengthy career, he has earned about 50 cents an hour.

But…

I would not have several copies of a beautiful hardback encyclopedia sitting on my shelves.

I would not have the professional achievement of editing a multivolume encyclopedia to add to my CV, which also makes the universities and colleges that employ us happy.

I would not have developed the scholarly network (much on social media) that I have as a result of my numerous interactions (most of them very nice) with so many historians while editing an encyclopedia.

Yet there is some pay involved. In my three encyclopedia projects, my initial advance, the money they give you after signing a book contract, ranged between $3,000 and $8,000 (this can obviously vary by press), depending on the scope of the project. In addition to this, you will receive some royalties on the back end, once your advance has been satisfied through initial sales. You will also get several copies of your encyclopedia, typically at least five copies, which is no small thing in light of the retail cost of hardback multivolume academic encyclopedias. They make great personalized Christmas gifts for loved ones (your parents or in-laws) and save one from having to buy something else.

What about contributors? What can they expect in terms of compensation?

Again, contributors definitely do not do it for the money. There usually isn’t any. Good publishers do allow a small budget, sometimes several thousand dollars depending on the scope of the project, for contributor compensation. You might, for example, have a $7,000 contributor budget you can oversee for a multivolume work, but 150 contributors. If you divided the money equally, they would each earn about $46 dollars (for authoring, probably, 3-4 short essays each). They would also have to wait a couple of years until the project is published before receiving their $46 check. Instead, what most publishers do is allow contributors to use a type of fake money that can be redeemed for books with the publisher, and, in my experience, it is usually at a 3-1 rate. For example, rather than paying a contributor $50 in cash, which is not enough to buy most academic books, much less the encyclopedia they are writing for, the editor can offer up to $150 in books with the publisher, which may be enough to purchase the one volume encyclopedia they are contributing to. Usually, editors develop a sliding scale, in which one is not paid for their first essay or two, and then they get incrementally more for each essay they publish after that. This allows the editor to offer a full hardback set of the encyclopedia (which can cost several hundred dollars) to contributors who author enough words to justify it. Those who do not qualify for a hardback copy of the encyclopedia will still get access to the e-book (all contributors) and usually some money to spend on press books. The most important thing for Ph.D. students is seeing themselves published and adding those lines to their CVs. Senior scholars have less motivation, but they understand the importance of contributing to such works in a more general sense and may call on you one day to contribute to something they are working on. You’ll owe them.

You learn a lot.

Let’s face it, if you devote many years to editing or authoring three multivolume historical encyclopedias, you learn a thing or two. My familiarity with World History, as a result of carefully editing, fact checking, and revising hundreds, if not thousands, of essays over the years on various World History topics, has vastly improved. I first noticed it in my teaching. Students, as they sometimes do, would ask me random off-the-wall questions about ancient China, or medieval sub-Saharan Africa, and, as a humble crusade historian, I increasingly found I could offer substantive, or at least coherent and helpful, responses. Encyclopedia editing, if done properly, ensures that you, as the editor, will have to immerse yourself into the assigned essays (many of which you will author yourself) in such a way that you will emerge with a broad knowledge base. Of course, it is knowledge that is not always very deep, as would be the case for your area of specialization, but more than helpful for teaching an undergraduate world history course.

A few final thoughts

It helps, I think, to have a good sense of humor if you choose to become an encyclopedia editor. You will, after all, likely have to deal with all sorts of people and personality types along the way (contributors, publishers, copy editors, etc…) and you will spend many late nights communicating with them by email in the ways I have described above. Be grateful that they are coming together to help make the project possible and show them good will.

I will close by noting that I do not intend to edit or involve myself with another encyclopedia project, so I figured I would offer some frank insights here. Of course, I told myself “Not again!” after my first and second multivolume encyclopedias were published. So, who knows?

[1] Mirabile dictu, this is the proper Latin plural for CV, but only for the insufferably pedantic, such as my dear friend Al Andrea, who read this essay and insisted on it.