“As I write these words, it is nearly time to light the lamps; my pen moves slowly over the paper and I feel myself almost too drowsy to write as the words escape me. I have to use foreign names and I am compelled to describe in detail a mass of events which occurred in rapid succession; the result is that the main body of the history and the continuous narrative are bound to become disjointed because of interruptions. Ah well, “’tis no cause for anger” to those at least who read my work with good will. Let us go on.”

Anna Comnena, Alexiad 13.6, trans. by E.R.A. Sewter

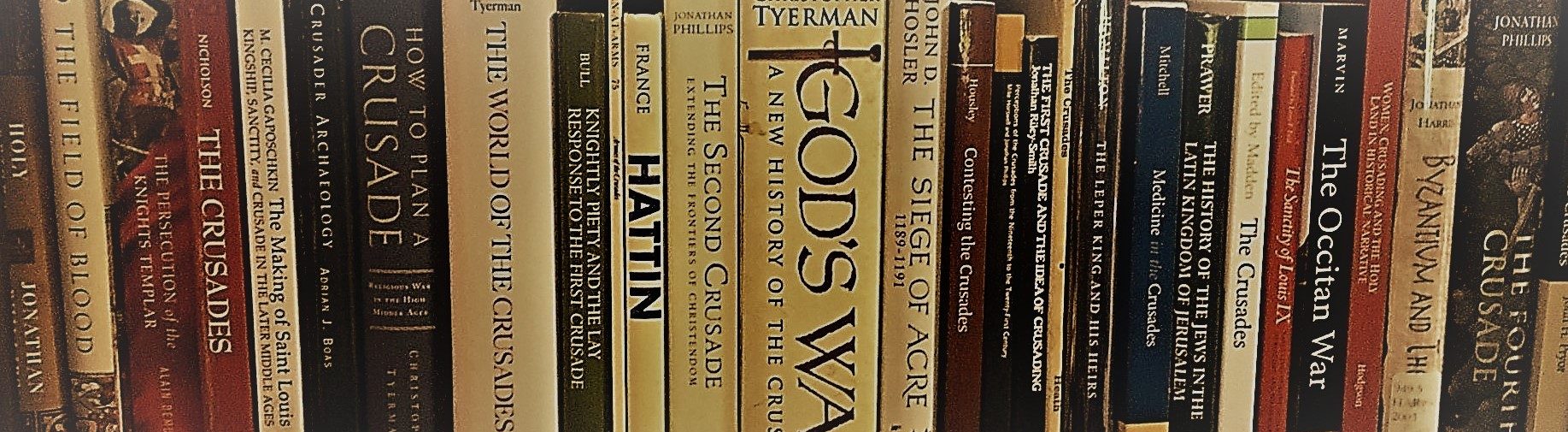

Provided here are the responses of 34 medieval historians who were asked to provide a list of the top ten “most important” books on the crusades. Many of them are leading scholars in the field. Hopefully, it will be a useful resource for both students and interested readers. For more information, please see the Crusade Book List Project and to see each historian’s list click on their name below (or you can scroll and browse through them below). Please hit the back button to return to the contributor’s list. Also, check back in the future for additional contributions that will be added over time. This will be an ongoing project.

See also: 15 “Most Important” Books on the Crusades

See also: The Most Influential Crusade Historians