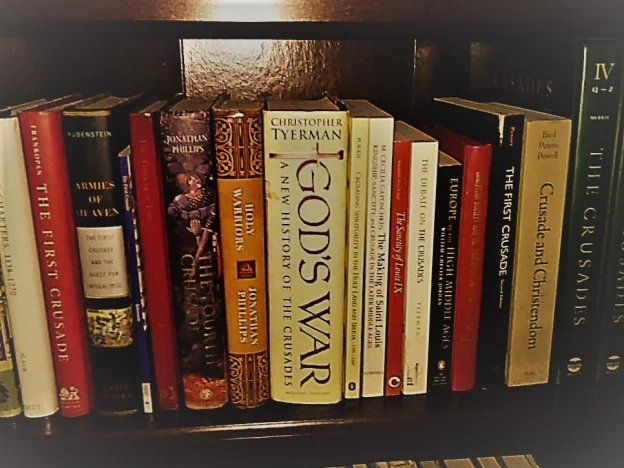

Above Image: Myself giving a lecture on the thorny topic of historic Bosnian and Serbian relations (Nov. 2015). Based on my past experiences with students, Jacksonville seems to have a large population of both Bosnian and Serbian immigrants, sometimes resulting in somewhat heated classroom discussions of related topics if not framed well from the outset.

—————-

I have seen many of my Facebook friends post stories about political or cultural bias on college campuses, sometimes expressing concern about what sort of education their children may be getting in the classroom, followed by expressions of lament for the high costs of college tuition on top of it. On rare occasions, I have also posted such stories and expressed similar incredulity, as in the case of a recent report about one university level U.S. history course that compared the “founding fathers” with the Westboro Baptist Church. When I did, it prompted a bit of a debate with one former academic, who defended the right of professors to use hyperbole to stir class discussion and thinking about historical events from different perspectives. I can appreciate the point more generally, yet in this particular case I see the rhetoric used (as reported) as too extreme, to the point of no longer really teaching “history” by modern professional standards. Yet, as I noted, some of my colleagues appear to disagree and have a more nuanced perspective.

As a result, I had been thinking about the topic of “objectivity” in the classroom when I came across a recently released statement by the American Historical Association issued in the wake of Donald Trump’s recent election victory. Consequently, I may have initially read it in a slightly different context than many of my fellow historians. It noted:

An unusually bitter and divisive election has been followed by continuing evidence of polarization to the point of harassment seldom seen in recent American history. The American Historical Association… condemns the language and harassment that have charred the American landscape in recent weeks. The AHA… [emphasizes] mutual respect and reasoned discourse—the ongoing conversation among historians holding diverse points of view and who learn from each other. A commitment to such discourse—balancing fair and honest criticism with inclusive practices and openness to different ideas—makes possible the fruitful exchange of views, opinions, and knowledge. The American Historical Association reaffirms its commitment to mutual respect, reasoned discourse, and appreciation for humanity in its full variety. We will strive to demonstrate these values in all aspects of practice, including in our roles as teachers, researchers, and citizens.

As I read these words, I wasn’t thinking so much about how historians dialogue with each other (which I can assure you is sometimes quite inflammatory), but with our students in the classroom, a captive audience, thinking these stated ideals would apply nicely there as well. The statement does, at the end, mention that these values should be demonstrated in our roles as teachers, after all, as well as more generally.

In response, I reached out to ten historians to see if they might offer some brief thoughts on the topic of “Objectivity in the Classroom.” To be clear, I fully realize that complete or “true” objectivity is not possible, but nevertheless there are things a professor can do to insure some degree of objectivity or neutrality (“as much as humanly possible”) in how they frame and discuss sensitive political, religious, or cultural topics in the classroom. It’s interesting to note that the AHA statement cited above nowhere uses the word “objectivity,” but does emphasize “mutual respect” and “reasoned discourse” in its place.

Consequently, I was curious to see how the other historians considered such issues.

Continue reading →